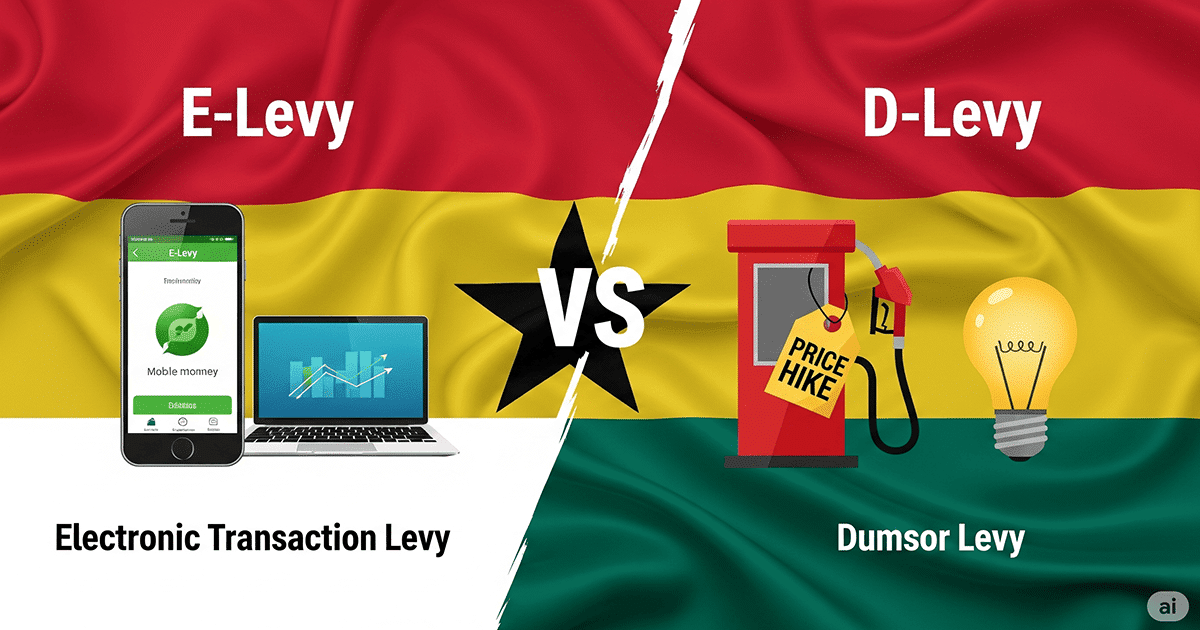

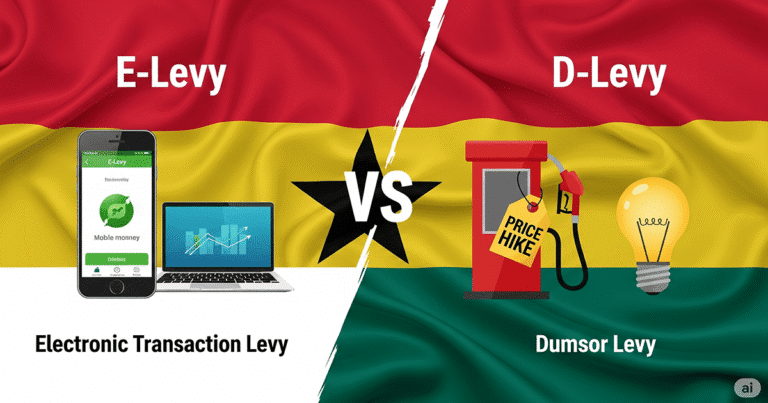

E-Levy and D-Levy. It’s been a tough couple of years for Ghana’s public finances. Governments over the years have been looking for new innovative ways to raise the needed revenue as the country has been kicked out of the international capital market. Out of that scramble have come two rather different taxes: the Electronic Transfer Levy (E-Levy) and, more recently, the Energy Sector Levy (already in existence, but the introduction of an additional GHS1 to support the fight against the energy crisis) D-Levy.

Both have stirred debate. Perhaps understandably. New taxes often do. But what’s interesting is how these two levies, introduced under different circumstances and with different targets in mind, have become the subject of public comparison. Some argue they’re similar in spirit. Others, me included, aren’t so sure. There’s something fundamentally different about how they function and what they try to tax.

So, I’ve been thinking: maybe it’s worth slowing down and really asking what these levies are. What kind of taxes are they? Whom do they affect? Are they fair? And more importantly, do they make sense?

First, the E-Levy.

The E-Levy came into effect in May 2022, and what it did was fairly straightforward, at least on paper: it imposed a 1.5% (later reduced to 1%) charge on certain electronic transfers: mobile money, bank-to-bank transactions, and a few others. The stated goal was to capture revenue from the informal sector, which, in Ghana, is quite large and largely untaxed.

But if we pause and ask a basic question, what exactly was being taxed?, things become less clear. It wasn’t income. It wasn’t consumption. It wasn’t wealth or capital gains. It was, quite literally, the act of moving money from one account to another. And that’s where many policy analysts raised their eyebrows.

You see, most taxes fit into familiar categories. Income taxes are based on what you earn. Consumption taxes like VAT are levied when you buy goods or services. Wealth taxes are based on what you own. But this? This was something else. It taxed movement, not substance.

From a policy standpoint, that’s tricky. It makes it harder to justify because the tax isn’t clearly tied to an economic activity that creates value. And perhaps even more concerning, it was flat. That is, everyone paid the same rate, regardless of whether they were transferring GHS100 or GHS20,000.

That flatness made the tax regressive. Low-income earners, who often use mobile money for day-to-day needs, ended up bearing a disproportionate burden. I remember seeing a colleague, a teacher, visibly frustrated when her transaction was taxed. “But it’s my own money,” she said. “I already paid tax when I earned it.” And, frankly, she had a point.

Beyond that, the E-Levy had the unfortunate effect of pushing people away from electronic payments. Usage dropped noticeably. People began withdrawing cash instead of transferring it, undermining both the revenue goals and the push toward a cashless economy. So in trying to modernize taxation, the policy may have actually slowed down financial inclusion.

Now, the D-Levy.

Fast forward to June 2025, and we have the D-Levy: a GHS1 per liter tax on petroleum products. Its purpose? To help pay down Ghana’s ballooning energy sector debt and, supposedly, support power sector stability (Dumsor must end; protestors YVONNE NELSON might be happy 😃).

At first glance, this looks more traditional. It’s a consumption tax. If you buy fuel, you pay. It’s simple, at least mechanically. And there’s something to be said for that. Unlike the E-Levy, this tax falls on a tangible good, fuel, which is consumed in measurable ways. That makes the base clearer and the rationale easier to explain.

Of course, it’s not perfect. No tax is. Fuel taxes, though progressive in a general sense because higher-income individuals tend to own and drive more cars, can have spillover effects. When transport becomes more expensive, prices of goods can creep up. And who ends up feeling that pinch first? Usually, those already struggling to keep up.

Still, the D-Levy doesn’t carry the same conceptual confusion as the E-Levy. We know what’s being taxed. And we know why. And I think that matters.

Another thing to consider is the link between the tax and its stated purpose. The D-Levy is, at least officially, earmarked for a specific issue: energy debt and the fight against almighty Dumsor. That creates a clearer policy chain: pay this tax, and (hopefully) the lights stay on. Whether that actually happens is another story. But in theory, it’s easier to build trust around a tax that has a specific, visible goal.

Public reactions? Mixed.

Neither levy was greeted with open arms. The E-Levy, in particular, sparked protests, petitions, and no small amount of political drama. The D-Levy hasn’t provoked quite as strong a response, but it hasn’t been embraced either. People are understandably tired of new taxes, especially when they don’t see a corresponding improvement in public services.

There’s also the issue of timing. Ghana has been dealing with inflation, currency depreciation (now appreciation because the finance minister Cassiel Ato Forson has turned the corner, in Ken Ofori-Atta’s voice), and fiscal belt-tightening. For many, a new fuel tax feels like salt in an open wound.

And yet, if we step back and compare, the D-Levy comes off as the more defensible policy, perhaps not in terms of popularity, but in terms of design. It sits within a known tax framework, it applies to consumption, and it targets a relatively wealthier subset of the population, at least more so than the E-Levy did.

So… which is better?

That depends on what you mean by “better.” If we’re talking about alignment with established taxation principles of clarity, fairness, and neutrality, then the D-Levy is clearly more coherent. It taxes a specific good tied to consumption, and it scales more naturally with wealth (even if indirectly).

But if we’re judging purely by impact on the average Ghanaian’s pocket? Then maybe both feel burdensome, just in different ways. The E-Levy chipped away at daily transactions, quietly but constantly. The D-Levy hits at the pump, where it’s more visible, more abrupt.

It’s not really about choosing one or the other. The better question might be, what kind of taxation culture are we trying to build? One that’s transparent, targeted, and tied to outcomes? Or one that scrapes from wherever it can, without much care for fairness or economic coherence?

That’s the real conversation, I think. Because it’s not just about raising money, it’s about how you raise it and who you ask to pay.

Final thought?

Ghana doesn’t lack options. But it does need more thoughtful tax policy, ones that don’t just react to crises but build public trust over time. And trust, in matters of taxation, is worth more than any levy ever will be.

I’m Prince Owusu-Ansah (Adewale).

Co-founder of Africa Policy Foundation

Plt 65, BIk B Kotei-Transformer, Kumasi

Today I enjoyed my fufu with goat soup from Accuzi Pup; you can join me tomorrow.

tay informed and inspired with Sabon News, where every story is crafted to connect you to the heart of global events and foster a deeper understanding of our shared humanity.